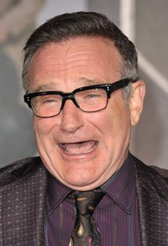

I have lost my doppelgänger. All my adult life I have been fated, due to oddly similar facial characteristics (from a certain angle, and especially lately with ever receding hairlines), to have been confused with Robin Williams. This happened most often in public settings, when I would detect strangers staring at me, whispering to a friend with a furtive nod in my direction. Because I too am in the film business, and frequently convey, superficially anyway, a somewhat antic temperament, the confusion happened a lot.

Occasionally I benefited from the resemblance: I was once whisked past a long line of waiting patrons upstairs at Chez Panisse, where the maître d’ greeted me warmly with “How nice to see you again!” and immediately seated my party at a prized table. I tried to convince myself and my impressed friends that he recognized me. But a few minutes later I saw the maître d’ scrutinizing me from afar: annoyed, even ashamed, that he had been taken in by an impostor. Hey, I hadn’t asked for the special attention. From everything I know about Robin Williams, I suspect he wouldn’t have either.

I never got the chance to ask Robin Williams if he too was plagued by this confusion—set upon by strangers who breathlessly wished to be greeting their spritely gay Jewish filmmaker friend, only to be disappointed that it was an international comic superstar. I did have the chance: In 1984, in a private airport lounge at SFO, I saw him lying across several seats, napping. I stared at my doppelgänger, living proof that we were two separate, distinct beings, our differences now magnified because I was looking for them. I didn’t have the heart to disturb him, just so we could gaze into each other’s funhouse-mirror reflection of ourselves. I let him sleep in peace.

I’d long gotten used to our resemblance, and confident enough in my own persona to laugh it off; but now, in these sad last few days, I find myself weirdly self-conscious. In public, I believe that somehow I am conjuring a ghost, and far too soon—one whose gifts, and struggles, were uniquely his, and not for me to impersonate, even unwittingly. I feel the absence of his comic brilliance as much as his adoring public does, with great pain, but also with a specific and peculiar pang: I am suddenly now a phantom limb, a presence at once comforting and disorienting, a reminder of what we had, and what we’ve lost.

I never got the chance to ask Robin Williams if he too was plagued by this confusion—set upon by strangers who breathlessly wished to be greeting their spritely gay Jewish filmmaker friend, only to be disappointed that it was an international comic superstar. I did have the chance: In 1984, in a private airport lounge at SFO, I saw him lying across several seats, napping. I stared at my doppelgänger, living proof that we were two separate, distinct beings, our differences now magnified because I was looking for them. I didn’t have the heart to disturb him, just so we could gaze into each other’s funhouse-mirror reflection of ourselves. I let him sleep in peace.

I’d long gotten used to our resemblance, and confident enough in my own persona to laugh it off; but now, in these sad last few days, I find myself weirdly self-conscious. In public, I believe that somehow I am conjuring a ghost, and far too soon—one whose gifts, and struggles, were uniquely his, and not for me to impersonate, even unwittingly. I feel the absence of his comic brilliance as much as his adoring public does, with great pain, but also with a specific and peculiar pang: I am suddenly now a phantom limb, a presence at once comforting and disorienting, a reminder of what we had, and what we’ve lost.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed