For many years I saved a phone message from Julia Child on my answering machine. Back then, in the early 1990s, I was a television producer at KQED, San Francisco’s public television station. Despite my frequent encounters with talented artists through my work, as well as a growing friendship with chef Jacques Pépin, with whom I had been producing several seasons of PBS cooking programs, I can still remember the shiver of excitement when I retrieved a message on my office voicemail which began, in that unmistakable forceful warble, “Hello Peter, it’s Julia Child!”

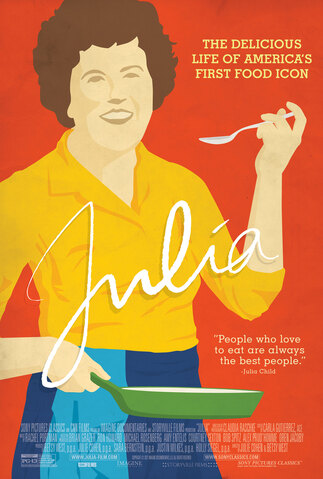

Photo: Brian Leatart/Sony Pictures Classics

Photo: Brian Leatart/Sony Pictures Classics My first thought was: ‘Of course it’s Julia Child! No one else on earth speaks like that. But why is she saying my name?’ The message went on at length; as it turns out, she wasn’t really interested in talking to me, she was calling because she knew I could pass along a message to her friend Jacques, who was taping shows in our San Francisco studio (this in the era before mobile phones). It ended, “Tell him I’ll be here in my office for, oh, I’d say an hour, an hour and a half…” I backed up the voicemail and replayed that last phrase, over and over. How often had I heard her use that very phrase on television, but referring to how long a roast should stay in the oven? “An hour, an hour and a half.” And now she was saying it to ME!

For years, I couldn’t bring myself to erase that mundane message. I am not generally a fanboy, but there was something about her folksy-but-refined lilt, and her matter-of-fact delivery of the eternal verities of cuisine and the clock, that I found irresistible: they were a touchstone to my own post-college years in Cambridge, Mass. (coincidentally, her hometown)—a time of my growing independence, when I learned to cook for myself and first discovered her TV shows and cookbooks. So I hung on to that message like a jewel.

For years, I couldn’t bring myself to erase that mundane message. I am not generally a fanboy, but there was something about her folksy-but-refined lilt, and her matter-of-fact delivery of the eternal verities of cuisine and the clock, that I found irresistible: they were a touchstone to my own post-college years in Cambridge, Mass. (coincidentally, her hometown)—a time of my growing independence, when I learned to cook for myself and first discovered her TV shows and cookbooks. So I hung on to that message like a jewel.

It turns out I was not alone: two decades later, while doing research for the American Masters documentary I was making about Jacques Pépin, I was digging through boxes of his archive now housed at the Boston University manuscript library, when I came upon several microcassettes of audiotape stashed among his correspondence and photos. On the cassettes’ tiny labels I recognized Jacques’ handwriting – he had written only one word: “Julia.” I felt again that sudden frisson of excitement from 20 years earlier, palms suddenly damp. Perhaps these were private conversations between them, or Jacques’ own confidential reminiscences about her? I returned the next day with a handheld dictation recorder that used the same size microcassettes, and, attaching a little Radio Shack earbud, I listened to those mystery tapes.

The tapes were answering machine cassettes. On them were a few banal messages to Jacques and his wife Gloria from Julia Child. No secret interviews, no long-lost brainstorms on how to make culinary history. Just phone messages. “Hi Jacques, I know we’re going to see each other Tuesday, but we better decide what we’re going to do.” “Jacques, it’s Julia, sending greetings to you before the holidays!” In his many boxes of stored memories and accolades—including his commendations from French presidents and treasured letters from his friends Craig Claiborne, James Beard, Danny Kaye—Jacques had saved nobody else’s phone messages, only Julia’s. They were a touchstone for him too: the everyday sound of a longtime friendship and professional collaboration. (I found a way to incorporate brief snippets of those tapes into the film I made, Jacques Pépin: The Art of Craft, which includes a segment on their working relationship.)

I’ve been thinking a lot about those phone messages—mine and Jacques’—since watching Julie Cohen’s and Betsy West’s new documentary Julia, which does a fine job capturing not only her professional and cultural accomplishments as a pathbreaker in the fields of American food and media, but also some of the personal idiosyncrasies and flaws that made her complex and unforgettable—someone whose voice you would want to save on a tape. It’s not only that she was a cultural icon with a famously imitated manner; she was a unique and formidable presence. I finally had the chance to meet her several times over the final decade of her life; in person, she managed to be warm, gracious, and often very funny, but with a barely disguised steely core of determination and focus—she could be flinty, a force you might not wish to cross.

That impression was reinforced over the years through reminiscences and anecdotes shared with me by Jacques and other frequent television colleagues of Julia. So I was relieved (if a bit surprised) to find that the recent documentary, while very affectionate and admiring of its subject, chose not be a hagiography, but a fully dimensional portrait that included some of her lesser-known traits: her salty language in private, her competitiveness, her occasionally retrograde references to gay men (despite the fact that so many of her culinary and television colleagues were gay). These are the warts that make people believably human, if not always 100% admirable. Jacques’ and my voicemails were the artifacts of a flesh-and-blood person, not an icon.

In my recollection of her, one of Julia’s qualities that both amused and dumbfounded me was her legendary resistance to anything resembling product placement or endorsement on her television programs. This trait could be seen as an admirable throwback to the purest noncommercial origins of public television, but it was also a sign of Julia’s orneriness. I recall one telling anecdote, which Jacques relayed to me:

from Julia & Jacques Cooking at Home (1999)

from Julia & Jacques Cooking at Home (1999) The PBS series that Jacques and Julia taped together in her Cambridge home was generously underwritten by a major California winery. On one taping day, several of the winery’s top executives paid a visit to the set and were watching the recording from the makeshift control room. Each episode would generally end with Jacques and Julia tasting the food they had made and then discussing the kind of wine they would recommend drinking with the meal. I know from my own experience with Jacques that he was especially mindful not to over-emphasize California wines in our series, let alone to blatantly recommend our sponsor’s wines, but in our many series together and in the one with Julia, it was tacitly accepted that occasionally a sponsor’s wine bottles would end up somewhere in the concluding scene, if it made gastronomic sense. On this day, Jacques, knowing full well how these expensive series get funded, figured the episode might warrant concluding with a nod to a California wine that happened to come from the sponsor, who was sitting in the control room.

When the moment arrived for the final shot, Jacques, with cameras rolling, turned to Julia and asked his leading question, “And what do you think we should drink?” to which Julia replied, “I think I’d like a beer!” Jacques froze momentarily, looked around the set, smiled, and said, “I don’t think we have beer here…” whereupon Julia reached under the table and brought out a bottle of beer, saying triumphantly, “I have some right here!” Jacques realized she had planned this little revolution all along.

Julia’s fierce individualism—to the point of being contrary—often gets sandpapered away in the popular image of the folksy French chef with the clumsy hands. But it is precisely that quality that compelled her to labor for more than a decade before finally publishing Mastering the Art of French Cooking, and to shatter the many obstacles and prejudices she faced as a woman, and later a senior, on television.

The fact that both Jacques Pépin and I would separately hang on to phone messages from Julia is testament not to her fame, but to her uniqueness. Despite the imitations and spoofs, despite her larger-than-life image and her impact on so much of American life, she was, in the end, herself.

When KQED changed its voicemail vendor, my saved message from Julia was vaporized. I was heartbroken. The jaunty message had been special to me not because it was important, but because it wasn’t: it was an ordinary artifact of an extraordinary person.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed