Traditionalists are often aghast when contemporary artists attempt to intervene into and transform iconic places—even temporarily. As a teenager, I remember the outcry in the Bay Area when the artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude proposed to erect their “Running Fence”—a 25-mile long shimmering strand of veils that rippled across the Sonoma hills to the sea, and stood for only two weeks. People scoffed at the wasteful effort, ridiculing the artists’ attempt to comment on, let alone improve, what nature had, in its glory, already made perfect. And yet whenever I meander through the grassy coastal hills near Bodega Bay, the image of that fence remains vivid. The transformation of the landscape seems to have had a potent afterlife in my unconscious: I round a corner, wondering if I might still glimpse it; lines of white sheep scattered across the hills bring to mind the desultory rambling of that fence; and actual wooden fences seem stolid and heavy in comparison to the linen veil that lasted only a fortnight. The work permanently shifted how I see the landscape. And that of course was the point—a shift in perception.

| I was reminded of this last week on a visit to Manhattan, when I stopped by the Guggenheim Museum: another iconic place, temporarily transformed in a way that I think will be hard to shake. James Turrell, an artist I especially like who works with light and volume, has taken as his canvas the legendary spiraling rotunda that constitutes the interior of Frank Lloyd Wright’s 1959 building. You’ve got to have some serious chutzpah (or substitute your foreign-sounding noun of choice…cojones? hubris?) to fiddle around with Wright’s legendary spherical volume, with its gently rising rampways that culminate in a spider-web dome window. |

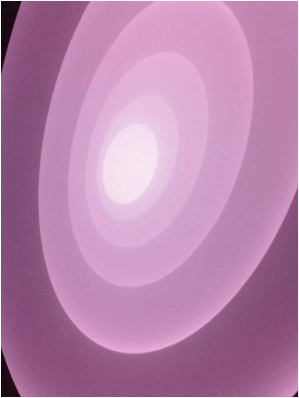

And yet Turrell has created something magnificent inside Wright’s space that obliterates the memory of it even while paying homage to it. Walking into the rotunda, one enters not a rounded architectural volume, but an enormous light chamber. Looking up, one sees not the spherical solidity of a building atrium, but a numinous void…a series of concentric ellipses, slowly shifting in hue, now gray, now rose, now indigo, but always receding in intensity toward a glowing white center. There is no sound track (other than the constant, and sometimes annoying, burble of visitors); and since the second week of the installation, padded mats have been tossed onto the floor to accommodate the inevitable impulse to gaze, supine, into the void.

As I stared, transfixed, into the light-space, I found myself disoriented—was this really the Guggenheim rotunda, now misshapen into an oval? Was I actually staring up into five stories of space, or was this somehow a flat surface, a screen with projected colors that told some kind of abstract narrative? And I realized that this disorientation was precisely the idea of Turrell’s work—it made you take a step away, even if unconsciously, from the known, rationally perceived world into a more ambiguous, unsettling, mysterious place.

Some have carped about the installation—offended by the excess of a gold-plated institution throwing a lot of money at a brand-name artist. Others find the whole idea an exercise in gilding the lily. The Guggenheim rotunda is already a masterwork of light and volume, so why make it another such space? But as I keep turning my thoughts back to that glowing elliptical teleidoscope, I realize that, as with the Sonoma hills, I will likely never be able to experience the Guggenheim in the same way again…the memory of those ellipses will always be vibrating at the fringes of my perception. And that alone makes this artwork a phenomenal achievement.

(Do you have a favorite—or failed—example of an artistic transformation? I. M. Pei’s Louvre pyramid? Something by Andy Goldsworthy? Feel free to add your own memory, comment or experience below!)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed